Visitor itinerary

The 1870–1871 war was the founding event that set the tone for Franco-German relations and paved the way for Europe’s future path. It effectively put an end to the diplomacy-centred balance of power known as the Concert of Europe, as well as the ‘repose of Europe’, ideas that did not resurface, in a different form, until the post-1945 period.

The conflict pitted France, a country that had spent several centuries building and consolidating its unity across a succession of political regimes, against Germany, a nation as yet unformed, comprising a collection of more recently emerged states.

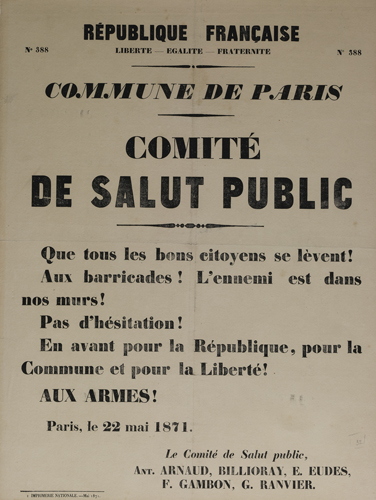

In France, despite the proclamation of the Republic, pre-existing social tensions and the patriotic fervour triggered by Napoleon’s defeat led to the Paris Commune and the outbreak of civil war. In Germany, victory served to unify the country, symbolised by the proclamation of the Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. A huge diversity and multiplicity of memories of the war exist on both sides, French and German, from official and personal sources. These recollections give us invaluable insights into the conflict’s lasting impact on European societies.

The chronology of these events should be placed within a long-term context that reveals their true span and origins, reaching back to 1864, a year that marked the start of the German unification wars, and 1875, which saw the ‘War in Sight’ crisis; their span stretches from the Wars of Liberation (1813–1815) and Congress of Vienna (1815) to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which brought World War I to a close.

In France, despite the proclamation of the Republic, pre-existing social tensions and the patriotic fervour triggered by Napoleon’s defeat led to the Paris Commune and the outbreak of civil war. In Germany, victory served to unify the country, symbolised by the proclamation of the Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. A huge diversity and multiplicity of memories of the war exist on both sides, French and German, from official and personal sources. These recollections give us invaluable insights into the conflict’s lasting impact on European societies.

The chronology of these events should be placed within a long-term context that reveals their true span and origins, reaching back to 1864, a year that marked the start of the German unification wars, and 1875, which saw the ‘War in Sight’ crisis; their span stretches from the Wars of Liberation (1813–1815) and Congress of Vienna (1815) to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which brought World War I to a close.

Shortcut

Eagle from the Flag of the 21st Line Infantry Regiment, 1860 model

Musée de l’Armée, Paris

Eagle from the Flag of the 21st Line Infantry Regiment, 1860 model

Musée de l’Armée, Paris© Paris, musée de l’Armée, Dist RMN-GP / Pascal Segrette